The Clifton Suspension Bridge is a testament to Victorian engineering and the visionary mind of Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Spanning the Avon Gorge, this iconic structure has become synonymous with Bristol. A recently unearthed letter from Brunel offers fresh insights into his aspirations and challenges during the bridge’s conception and construction.

A Visionary’s Ambition

In the early 19th century, the need for a bridge connecting Clifton in Bristol to Leigh Woods in North Somerset became evident. The cliffs of the Avon Gorge presented a formidable challenge, deterring traditional bridge designs. In 1753, Bristolian merchant William Vick bequeathed £1,000, intended to accumulate until it could fund a stone bridge across the gorge. By the 1820s, with the fund having grown, the idea was revisited, but a stone bridge was deemed impractical due to the site’s topography. This set the stage for a more innovative solution.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel, a burgeoning engineer, saw this as an opportunity to make his mark. In 1830, at just 24, he submitted his design for a suspension bridge, envisioning it as a “splendid ornament” for the city. Brunel’s design featured Egyptian-style towers and a span of 702 feet, making it the longest in the world then. Despite initial setbacks, including rejecting his design in favour of more conservative proposals, Brunel’s persistence paid off. After a second competition in 1831, his design was finally accepted.

Challenges and Setbacks

The path to realizing Brunel’s vision was fraught with obstacles. The Bristol Riots of 1831 halted initial construction efforts, and financial difficulties plagued the project for years. Brunel’s recently discovered letter, addressed to the project trustees, sheds light on his frustrations during this period. He expressed concerns over funding and the technical challenges of constructing such an ambitious structure. In the letter, Brunel wrote, “The obstacles are indeed great, but my conviction remains unshaken that this bridge will not only serve a practical purpose but also stand as a monumental achievement in engineering.”

Tragically, Brunel did not live to see the completion of his masterpiece. He passed away in 1859, and the project remained unfinished. However, his vision did not die with him. Engineers John Hawkshaw and William Henry Barlow took up the mantle, modifying Brunel’s original design to incorporate advancements in materials and construction techniques. Their efforts culminated in the bridge’s completion in 1864, five years after Brunel’s death.

Architectural and Engineering Marvel

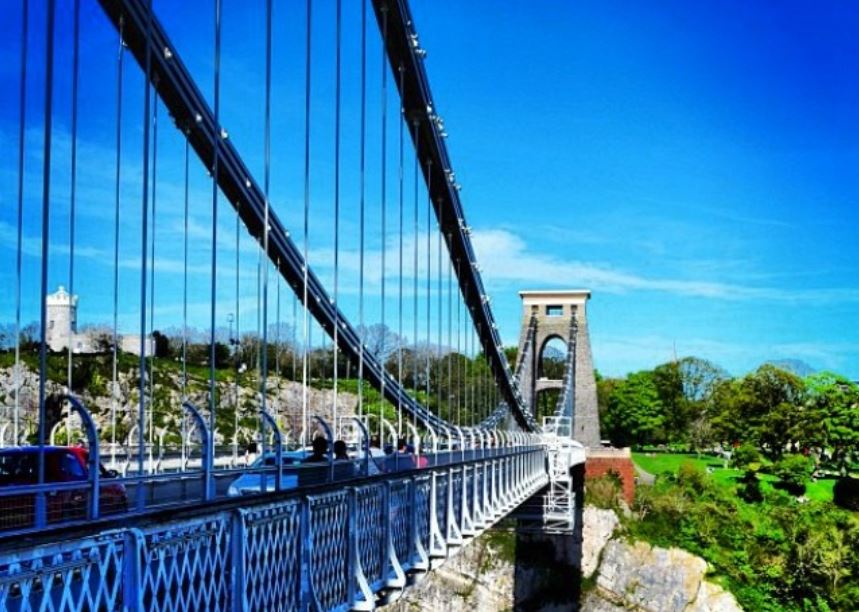

The Clifton Suspension Bridge’s design harmoniously blends aesthetics and functionality. Though similar in size, the towers differ in design; the Clifton tower features side cut-outs, while the Leigh Woods tower boasts pointed arches atop a red sandstone-clad abutment. This subtle asymmetry adds to the bridge’s unique charm.

One of the bridge’s most remarkable features is its use of roller-mounted “saddles” atop each tower. These allow the wrought iron chains to move slightly, accommodating the loads and stresses as traffic passes over. This innovation ensures the bridge’s longevity and stability. The deck, originally made of wooden planks, has undergone several refurbishments to meet modern standards, yet the bridge retains much of its original character.

Cultural and Historical Significance

Since its opening, the Clifton Suspension Bridge has been more than just a means of crossing the Avon Gorge. It has become an enduring symbol of Bristol’s industrial heritage and innovative spirit. The bridge has witnessed numerous significant events, including the first modern bungee jump in 1979 and serving as a backdrop for the last Concorde flight in 2003. Its silhouette graces countless postcards, artworks, and photographs, reinforcing its status as an iconic landmark.

The discovery of Brunel’s letter adds a personal dimension to the bridge’s history, offering a glimpse into the determination and passion that drove one of Britain’s most outstanding engineers. It serves as a reminder of the challenges faced during the bridge’s construction and the unwavering commitment to overcoming them.

Preservation and Legacy

Today, the Clifton Suspension Bridge is maintained by a charitable trust, ensuring that this historic structure continues to serve both functional and educational purposes. The bridge attracts visitors worldwide, drawn by its architectural beauty and panoramic views of the surrounding landscape. Academic programmes and visitor centres provide insights into the bridge’s construction, history, and Brunel’s genius.

In recent years, efforts have been made to preserve the bridge’s physical structure and historical records. The letter from Brunel, now housed in the University of Bristol’s Special Collections, is a valuable addition to the archive, offering scholars and enthusiasts deeper insights into the bridge’s storied past.